Într-una din zilele trecute am descoperit complet întâmplător niște traduceri la scrisorile lui Vincent van Gogh către fratele lui, Theo.

Las mai jos câteva fragmente fascinante pe care le-am subliniat într-una din ele, datată iunie 1880. Vincent avea 27 de ani, trăise ultimii ani în sărăcie extremă și își căuta vocația, se simțea măcinat și nu știa ce să facă – era chiar înainte să se dedice artei. Înainte de această scrisoare, a existat o pauză de un an în corespondența dintre el și fratele lui, din cauza unor tensiuni și conflicte în familie legate de alegerile lui Vincent (tatăl lui plănuia să-l interneze la un azil de nebuni). Printre altele, explică și de ce renunțase la studiile universitare și îi mulțumește fratelui său, care l-a susținut financiar:

„I, for one, am a man of passions, capable of and liable to do rather foolish things for which I sometimes feel rather sorry. I do often find myself speaking or acting somewhat too quickly when it would be better to wait more patiently. […] Now that being so, what’s to be done, must one consider oneself a dangerous man, incapable of anything at all? I don’t think so. But it’s a matter of trying by every means to turn even these passions to good account. For example, to name one passion among others, I have a more or less irresistible passion for books, and I have a need continually to educate myself, to study, if you like, precisely as I need to eat my bread. You’ll be able to understand that yourself. When I was in different surroundings, in surroundings of paintings and works of art, you well know that I then took a violent passion for those surroundings that went as far as enthusiasm. And I don’t repent it, and now, far from the country again, I often feel homesick for the country of paintings.”

„Now the man who is absorbed in all that is sometimes shocking, to others, and without wishing to, offends to a greater or lesser degree against certain forms and customs and social conventions. It’s a pity, though, when people take that in bad part. For example, you well know that I’ve frequently neglected my appearance, I admit it, and I admit that it’s shocking. But look, money troubles and poverty have something to do with it, and then a profound discouragement also has something to do with it, and then it’s sometimes a good means of ensuring for oneself the solitude needed to be able to go somewhat more deeply into this or that field of study with which one is preoccupied.”

„Perhaps you’ll say, but why didn’t you continue as people would have wished you to continue, along the university road?

To that I’d say only this, it costs too much and then, that future was no better than the present one, on the road that I’m on. But on the road that I’m on I must continue; if I do nothing, if I don’t study, if I don’t keep on trying, then I’m lost, then woe betide me. That’s how I see this, to keep on, keep on, that’s what’s needed.”

„Well, then, what can I say; does what goes on inside show on the outside? Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney and then go on their way. So now what are we to do, keep this fire alive inside, have salt in ourselves, wait patiently, but with how much impatience, await the hour, I say, when whoever wants to, will come and sit down there, will stay there, for all I know? May whoever believes in God await the hour, which will come sooner or later.”

„So you mustn’t think that I’m rejecting this or that; in my unbelief I’m a believer, in a way, and though having changed I am the same, and my torment is none other than this, what could I be good for, couldn’t I serve and be useful in some way, how could I come to know more thoroughly, and go more deeply into this subject or that? Do you see, it continually torments me, and then you feel a prisoner in penury, excluded from participating in this work or that, and such and such necessary things are beyond your reach.”

„Because there are idlers and idlers, who form a contrast.

There’s the one who’s an idler through laziness and weakness of character, through the baseness of his nature; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.

Then there’s the other idler, the idler truly despite himself, who is gnawed inwardly by a great desire for action, who does nothing because he finds it impossible to do anything since he’s imprisoned in something, so to speak, because he doesn’t have what he would need to be productive, because the inevitability of circumstances is reducing him to this point. Such a person doesn’t always know himself what he could do, but he feels by instinct, I’m good for something, even so! I feel I have a raison d’être! I know that I could be a quite different man! For what then could I be of use, for what could I serve! There’s something within me, so what is it! That’s an entirely different idler; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.”

Credite:

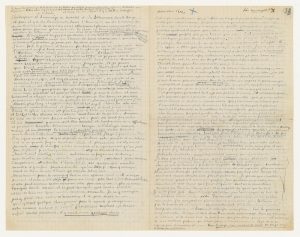

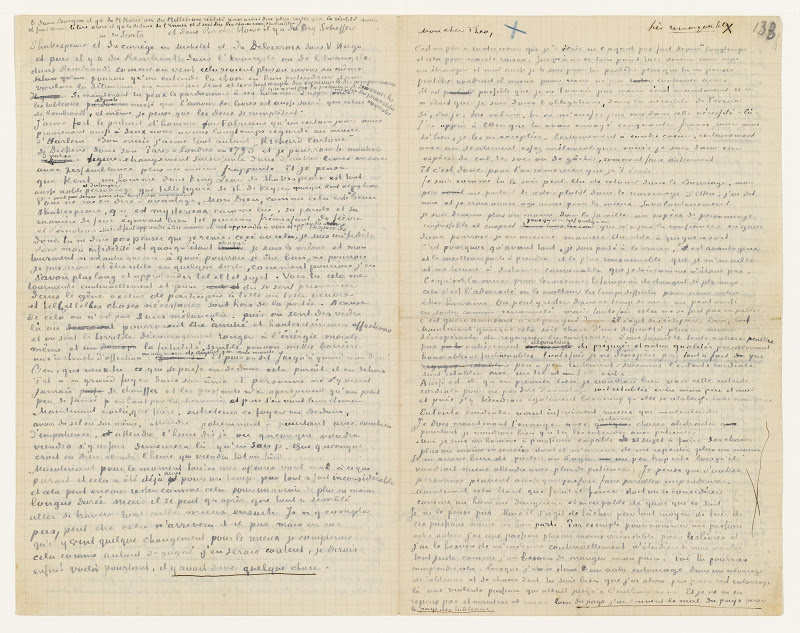

- Foto: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

- Scrisoarea integrală și traducerea: Van Gogh To Theo van Gogh letter 155. Cuesmes, between about Tuesday, 22 and Thursday, 24 June 1880.